While more than one million Irish people starved and another million plus were exiled aboard coffin ships, the Vandeleur family of Kilrush dined, sailed, and celebrated with grotesque indifference. Their actions during Ireland’s darkest years were not mere oversight or misunderstanding – they were acts of elitist disregard against a backdrop of scarcity, severe hardship and death.

The Yachts, the Wine, and the Wasted Lives

In December 1841, Crofton Moore Vandeleur launched the Lady Grace, a schooner named after his wife, with artillery salutes, brass bands, and copious wine. The ship was christened by Lady Grace herself with a bottle of champagne, broken across the bow. That evening, Vandeleur held a banquet at Lomas’s Hotel for the local gentry, replete with lavish dishes, endless drink, and patriotic toasts to the Queen.

Contrast this with the fate of Kilrush’s poor: mass evictions, destroyed and crumbling houses (“teach leagtha”), and destitution. Thousands would be buried in unmarked graves.

Death by Landlordism

Colonel Crofton Vandeleur – landlord, yachtsman, Poor Law Guardian – was a man who evicted thousands to certain starvation and death and then went sailing and hosted lavish dinners.

The heartless indifference of his flamboyant leisure is breathtaking. In mid-1846, during one of the worst years of hunger, Vandeleur returned to Kilrush by yacht, partying with his sails full while his evicted tenants’ stomachs were empty.

In 1848, while hunger spread like wildfire, Crofton Vandeleur drove more than 4,000 men, women, and children from their homes—knowing full well that eviction now meant hunger, despair, and likely death.

But the Vandeleurs didn’t just evict them. They “tumbled” the houses – flattening them to the ground to ensure no one could return. Families were left to the elements, forced to dig holes in ditches, hedges, and crumbling banks – anywhere they might find shelter from the wind, the rain, and the cold.

One official wrote: “I have visited the waste houses from which these wretched creatures have been driven… in many cases the inmates had taken shelter in the ruins, or in ditches, or behind hedges, without roofs or covering of any kind.” – Captain Arthur Kennedy, 1848.

By 1849, with over 14,000 people in the Kilrush Union still needing aid, the Vandeleur-led board slashed relief. When Crofton Vandeleur appeared in public, crowds threw mud at him, for it was all they had. Throwing mud was not enough then and isn’t enough now.

Partying Through the Mass Starvation

In 1853, while Kilrush still reeled from death, starvation, and forced emigration on coffin ships, Crofton Vandeleur hosted a Shannon regatta. His newest yacht, Caroline (yes, yet another new yacht!), was described as “tastefully fitted” for the festivities.

No mention was made of the famine-dead. No memorial. No prayer. Only a celebration of the landed gentry aboard their custom made yachts, sipping champagne, oblivious and indifferent to the suffering all around.

In 1857, to celebrate the 21st birthday of his son Hector, the Vandeleurs held a three-day spectacle: two balls, fireworks, parades, races, and banquets. As champagne flutes clinked and rockets lit the night sky over Kilrush House, the mass famine graves at nearby Shanakyle lay in silent darkness.

On Vandeleur estates, half the population had been wiped out – more than 20,000 dead from starvation or famine-related disease, another 20,000+ forced to emigrate as penniless exiles – and the Vandeleurs partied on.

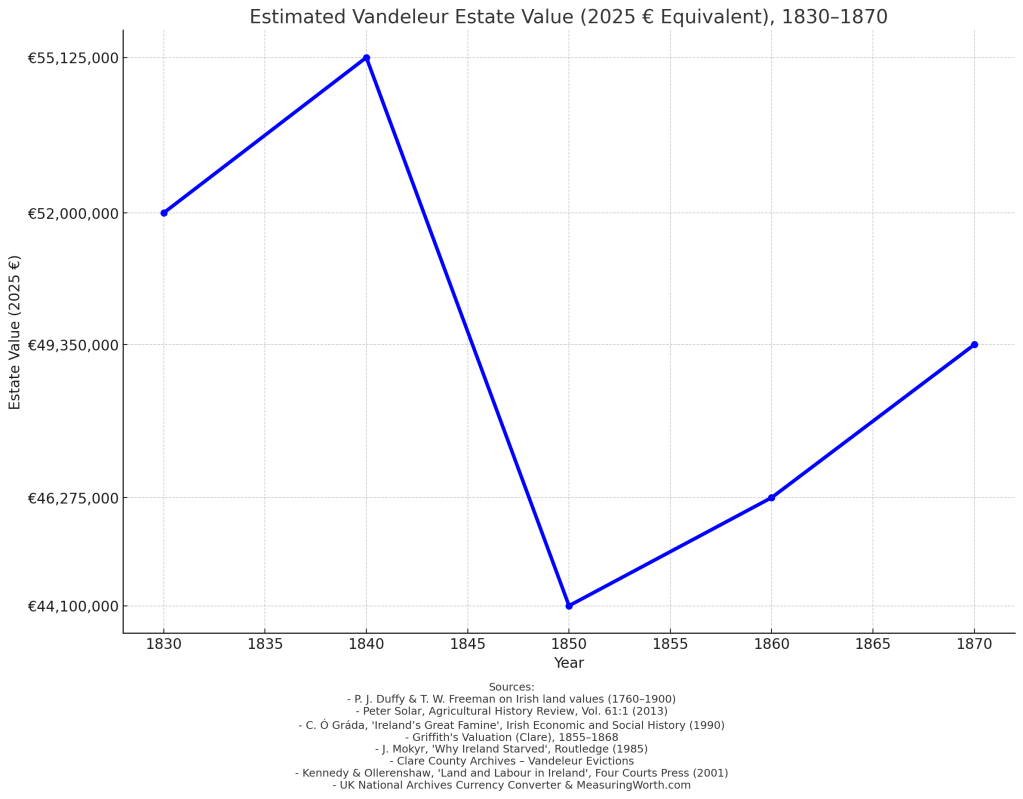

While their tenants starved, the Vandeleurs—one of the richest landowning families in Ireland—prospered. Though their estate income dipped during the worst famine years, their wealth rebounded swiftly after 1850. By the 1860s, their fortunes were again soaring.

History’s Verdict

This is not a story of complexity or nuance. This is a story of one class that buried the other – with pomp, with cruelty, and with no apology. While mothers and children were evicted and left to rot in ditches, the Vandeleurs launched yachts and toasted the Queen.

The area under the direct and complete control of the Vandeleurs, the Kilrush Poor Law Union, became a notorious epicenter of suffering culminating in the death of tens of thousands.

The Kilrush Poor Law Union had a pre-famine population of about 82,000 people. By 1851, the population of the Kilrush Union had fallen by nearly 40,000. It is estimated that in the Kilrush Union alone at least 20,000 people starved or died of famine-related disease, possibly closer to 25,000.

This Wasn’t Just Inequality — It Was Engineered Injustice

The Vandeleurs were not benign landlords caught in hard times. Far from it.

They were among the top 0.1% of income earners in Ireland, while their tenants languished in the bottom 5%—a brutal imbalance maintained by law, politics, and power. This was not passive inequality. It was a system engineered to enrich the few while depriving and breaking the many.

It’s worth repeating: 20,000 people died on the Vandeleur estates from starvation or disease. Another 20,000 were forced into exile—penniless, desperate, forgotten. Half the population disappeared. And through it all, the Vandeleurs prospered.

Even as their income dipped during the famine, their wealth rebounded swiftly after 1850, with estate values and personal fortunes climbing. They hosted balls, banquets, fox hunts and regattas—social spectacle built on mass suffering.

Today, their name still crowns the Vandeleur Walled Garden in Kilrush—a “heritage” attraction presented in sanitized font. But the wall was no mere ornament. It was built to keep the starving out—to protect fruit, herbs, and flowers grown not for the people, but for the “Big House.”

This is not heritage.

This is whitewashed history.

In using the Vandeleur name, we remember and honour the Vandeleurs.

While marginalizing their victims. How can anyone be okay with this?

Let us resolve to let no flower grow here without remembering victims buried in the mass graves beneath the soil of Kilrush.

CHANGE THE NAME!

CHANGE THE NAME!

GOOD GOD ALMIGHTY, CHANGE THE NAME!

The Vandeleur name still hangs over a public garden in Kilrush—while their victims lie in mass graves, their names lost and forgotten.

We call for a new name and a permanent memorial to those who suffered and died under Vandeleur control during the Great Hunger.

Add your name. Speak for the silenced.